Екінші тұрақсыз кезең - Second Stadtholderless period

The Екінші тұрақсыз кезең немесе Эра (Голланд: Tweede Stadhouderloze Tijdperk) - бұл голланд тіліндегі белгілеу тарихнама арасындағы өлімнің арасындағы кезең stadtholder Уильям III 19 наурызда,[1] 1702 ж. Тағайындау Уильям IV барлық провинцияларда генерал-капитан ретінде Нидерланды Республикасы 1747 ж. 2 мамырда. Осы кезеңде стадтолдер кеңесі провинцияларда бос қалды Голландия, Зеландия, және Утрехт Дегенмен, басқа провинцияларда бұл кеңсені әртүрлі кезеңдерде Нассау-Диц үйінің мүшелері толтырды (кейінірек Оранж-Нассау деп аталды). Осы кезеңде Республика өзінің ұлы державалық мәртебесінен және әлемдік саудадағы басымдығынан, процестер қатар жүретін процестерден айырылды, ал соңғысы біріншісіне себеп болды. Экономика едәуір құлдырап, теңіз провинцияларында индустрияландыру мен деурбанизацияны тудырғанымен, рентье-класс капиталдың ірі қорын жинақтап отырды, ол республиканың халықаралық капитал нарығында жетекші позицияға негіз болды. Кезеңнің аяғындағы әскери дағдарыс барлық провинцияларда Қатысушы мемлекеттер режимінің құлдырауына және Стадтхолдаттың қалпына келуіне себеп болды. Алайда, жаңа стадтлер диктаторлық дерлікке ие болғанымен, бұл жағдайды жақсартпады.

Фон

Тарихнамалық жазба

Шарттары Бірінші тұрақсыз кезең және екінші стадхедсыз кезең 19 ғасырда, ұлт тарихын жазудың ең гүлденген кезеңінде голланд тарихнамасында өнер терминдері ретінде қалыптасты, сол кезде голланд тарихшылары даңқты күндеріне мұқият қарады. Нидерланд көтерілісі және Голландиялық Алтын ғасыр және кейінгі жылдары «не болды» деп іздеген ешкілерді іздеді. Оранж-Нассаудың жаңа патшалық үйінің партизандары, ұнайды Гийом Грин ван Принстерер Республика кезінде шынымен де орангисттік партияның дәстүрлерін жалғастырушылар, тарихты апельсин үйінің тұрақшыларының (фриздік Надсау-Дицц үйінен шыққан фриздік тұрақшылардың ерліктері туралы қаһармандық баяндау ретінде баяндайды. Апельсин-Нассау үйі аз танымал болды). Осы тұрақтыларға кедергі болған кез келген адам, олардың өкілдері сияқты Қатысушы мемлекеттер, осы романтикалық әңгімелердегі «жаман жігіттер» рөлін өте жақсы орындады. Йохан ван Олденбарнвельт, Уго Гроциус, Йохан де Витт, бірақ іс жүзінде жын-перілер болмаса да, кейінірек тарихшылар жасауға дайын болғаннан гөрі өте қысқа болды. Аз танымал регенттер кейінгі жылдар тіпті жаман болды. Джон Лотроп Мотли, 19 ғасырда американдықтарды Голландия Республикасының тарихымен таныстырған, осы көзқарас қатты әсер етті.[2]

Повестьтің негізгі мазмұны: стадтерлер елді басқарған кезде бәрі жақсы болатын, ал егер мұндай батырлар гумрум регенттерімен ауыстырылғанда, мемлекет кемесі тарихтың жартастарына қарай жылжыды. Үстірт қарағанда, орангист тарихшыларда бір мәселе бар сияқты көрінді, өйткені екі кезең де дау-дамаймен аяқталды. Терминнің теріс мағынасы сондықтан лайықты болып көрінді. Алайда, басқа тарихшылар сұрақ белгілерін Орангистер тұжырымдаған себеп-салдар процесінің қасына қойды.

Алайда, бұл эмоционалды және саяси жүктелген термин әлі күнге дейін тарихи міндеттердің тарихи белгісі ретінде орынды ма деп сұрауға болады. периодтау ? Ұзақ мерзімді қолданыстағы жалпы тілмен айтқанда, мұндай өмір сүру құқығы орныққанынан басқа, бұл сұраққа оң жауап берілуі мүмкін, өйткені белгілі болғандай, болмауы Тұрақты ұстанушы шынымен де осы тарихи кезеңдердегі Республика конституциясының (оң қабылданған) принципі болды. Бұл Де Виттің «Нағыз бостандықтың» негізі болды, оның бірінші кезеңдегі оның қатысушы мемлекеттер-режимінің идеологиялық тірегі болды және екінші кезеңде солай қайта жанданады. 19 ғасырдағы әйгілі голланд тарихшысы Роберт Фруин (оны шамадан тыс орангисттік жанашырлықпен айыптауға болмайды) «тұрақсыз режим«кезеңдер үшін, біз тек жапсырмамен ғана айналыспайтындығымызды, бірақ тарихи жағдайда« айнымас кезең »мағынасын беретін тарихи жағдайдың болғанын баса көрсету үшін.[3]

Уильям III-нің стадхоляты

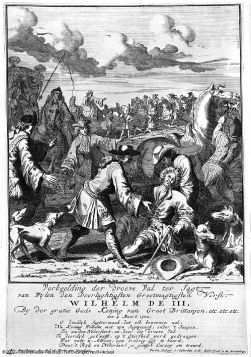

Кезінде 1672 жылғы француздар шапқыншылығына реакциядағы халықтық көтеріліс Франко-голланд соғысы, қатысушы мемлекеттердің режимін жойды Үлкен зейнеткер Йохан де Витт (аяқталатын Бірінші тұрақсыз кезең ) және билікке Оранждың Уильям III сыпырып алды. Ол 1672 жылы шілдеде Голландия мен Зеландияда стадтхолдер болып тағайындалды және өзінен бұрынғылардан әлдеқайда асып түскен өкілеттіктерге ие болды. Кезде оның позициясы алынбайтын болды Нидерланды генерал-штаттары оған 1672 жылы қыркүйекте Голландиядағы ірі қалалардың үкіметтерін тазартуға өкілеттік берді регенттер Қатысушы мемлекеттердің өкілдіктері болып табылады және оларды жақтаушылармен алмастырады Orangist фракция. Оның саяси позициясы 1674 жылы Голландия мен Зеландиядағы ерлер қатарында өзінің болжамды ұрпақтары үшін мұрагердің кеңсесі мұрагерлікке айналған кезде одан әрі нығайтылды (Кеңсе 1675 жылы Фрисландия мен Гронингендегі Нассау-Диц үйінің ұрпақтары үшін мұрагерлікке айналды). , Голландиядан фриздік егемендікке династиялық қол сұғушылықты тексеру мақсатында).

1672 жылы француздар басып алған провинцияларды реадмиссия кезінде 1674 жылдан кейін Одақ құрамына қабылдады (оларды басып алу кезінде генерал штаттарға тыйым салынды), бұл провинциялар (Утрехт, Гелдерланд және Оверейссель) саяси төлемдер төлеуге мәжбүр болды. деп аталатын түрдегі баға Regeringsreglementen (Үкіметтік ережелер) Уильям оларға жүктеген. Мұны оған осы провинциялардағы провинциялық деңгейдегі көптеген шенеуніктерді тағайындауға және қалалық магистраттар мен магистраттардың сайлануын бақылауға құқық берген органикалық заңдармен салыстыруға болады (балжуалар) ауылда.[4]

Көбісі бұл оқиғаларды стадтхолдер кеңсесі (кем дегенде Голландия мен Зеландияда) «монархиялық» болып қалыптасады деп қате түсіндірді. Алайда бұл сот түсініспеушілік болар еді, бірақ сот шешім қабылдаған сот шешімді түрде «князьдық» жағын алды (бұл Уильямның атасы кезінде болған сияқты) Фредерик Генри, апельсин ханзадасы ). Егер Уильям мүлдем монарх болса, бұл ресми және саяси тұрғыдан әлі де күрт шектеулі өкілеттіктерге ие «конституциялық» болды. Бас штаттар республикада егемендігін сақтады, басқа мемлекеттер келісімшарттар жасасқан және соғыс немесе бейбітшілік жасаған ұйым. Провинциялардың егемендік үстемдігіне деген көзқарастар, Де Витт режиміндегідей, қайтадан конституциялық теориямен ауыстырылды Морис, апельсин ханзадасы, режимін құлатқаннан кейін Йохан ван Олденбарнвельт 1618 жылы, онда провинциялар, кем дегенде, белгілі бір жағынан «Жалпыға» бағынышты болды.

Стадтхольдердің жаңа, кеңейтілген артықшылықтары көбінесе оның өкілеттіктерін қарастырды патронат және бұл оған мықты қуат базасын құруға мүмкіндік берді. Бірақ оның күшін көбіне басқа күш орталықтары тексерді, әсіресе Голландия штаттары және осы провинция құрамындағы Амстердам қаласы. Әсіресе, бұл қала Уильямның саясатына кедергі келтіре алды, егер олар оның мүдделеріне қайшы келеді деп есептелсе. Бірақ егер олар сәйкес келсе, Уильям кез-келген оппозицияны жеңе алатын коалиция құра алды. Бұл, мысалы, 1688 жылдың жаз айларында Амстердамды Англияға басып кіруді қолдауға көндірген кезде, кейіннен Даңқты революция және Уильям мен Мэридің Британ тағына отыруы.

Осыған қарамастан, бұл оқиғалар Уильямның (және оның достары, мысалы, Үлкен зейнеткер сияқты) болды Гаспар Фагел және Уильям Бентинк ) оның «монархиялық билікті» жүзеге асыруына байланысты емес, сендіру күштері мен коалиция құру шеберлігі. Республиканың бас қолбасшысы болғанымен, Уильям жай басып кіруге бұйрық бере алмады, бірақ генерал-штаттар мен Голландия штаттарының (іс жүзінде қоғамдық әмиянның бауларын ұстаған) рұқсатын қажет етті. Басқа жақтан, 1690 жылдардағы оқиғалар жобаларына қарама-қарсы бағытталған сыртқы саясат төңірегінде Нидерланды Республикасында үлкен консенсус жасауға көмектесті Людовик XIV Франция және осы мақсатта бұрынғы қас жау Англиямен тығыз одақтастықты сақтау, сонымен қатар Уильям өмірінің соңына қарай ол ел қайтыс болғаннан кейін оның мүдделерін міндетті түрде қоймайтын адам басқаратыны белгілі болған кезде. Бірінші республика (Уильям айтқандай).

Бұл үлкен консенсус, алайда, сарай қызметкерлерінің құлдық сиқырлылығының жемісі емес, Нидерланд үкіметтік орталарында бұл ең болмағанда сыртқы саясат саласында ұстанған дұрыс саясат екендігі туралы шынайы интеллектуалды келісім болды. Бұл ішкі саясат саласына барлық жағынан қатысты болмауы керек және бұл 1702 жылдың басында Уильям кенеттен қайтыс болғаннан кейінгі оқиғаның барысын түсіндіруі мүмкін.

Уильям III мұрагері

Ол қайтыс болған кезде Уильям Англия, Шотландия және Ирландия королі болған. The 1689 және 1701. Қондырғы актісі осы патшалықтардағы мұрагерлікті жеңгесі мен немере ағасының қолына мықтап тапсырды Энн. Алайда оның басқа атақтары мен кеңселеріне ауысуы онша айқын болған жоқ. Баласыз болғандықтан, Уильям кез-келген белгісіздікке жол бермеу үшін өзінің соңғы өсиетінде ережелер жасауға мәжбүр болды. Шынында да, ол жасады Джон Уильям Фрисо, апельсин ханзадасы, отбасының кадет бөлімінің бастығы, жеке және саяси жағынан оның жалпы мұрагері.

Алайда, егер оның апельсин ханзадасына байланысты титулдар мен жерлердің кешенін өз қалауынша билік етуге құқығы болса, күмән туындады. Ол сөзсіз білгендей, атасы Фредерик Генри жасады fideicommis (Төлем құйрығы ) оның еркінде когнатикалық сукцессия Апельсин үйіндегі жалпы сабақтастық ережесі ретінде өз жолында. Бұл ереже үлкен қызының еркек ұрпағына мұрагерлік берді Нассаудың Луис Анриетта егер оның жеке еркектері жойылып кетсе. (Ол кезде Фредерик Генри жалғыз ұлы қайтыс болды Уильям II, апельсин ханзадасы әлі де заңды мұрагері болған жоқ, сондықтан егер ол мұраның алыс туыстарының қолына түсуіне жол бергісі келмесе, сол кезде бұл мағынасы болды). Мұндай мұрагерлік мұраның тұтастығын қамтамасыз ету үшін ақсүйектер ортасында кең таралған. Мәселе мынада еді: жалпы көзқарас бойынша мұрагерлік мұраны иеленушілердің оны өз қалауынша билік ету құқығын шектейді. Уильям бұл ережені жоққа шығарғысы келген шығар, бірақ оның ерік-жігері дау-дамайға осал болды.

Фредерик Генридің әрекеті, Луис Хенриеттің ұлы, оның пайдасына пайда болған тараптың келіспеушілігімен болды. Фредерик І Пруссия. Бірақ Фредерик Уильямның еркіне қарсы шыққан жалғыз адам емес. Фредерик Генридің әрекеті апельсин ханзадасы атағының алдыңғы иегерлерінен басталған ұзақ жолдардың соңғысы болды. Шалонның Ренесі, жиеніне атақ беру арқылы әулетті құрған Уильям үнсіз, талапкерлердің көпшілігінің атасы. Рене еркек тегі жойылып кетуі мүмкін болған жағдайда, жиенінің әйел жолын жалғастырушы болды. Бұл жойылды агротикалық сабақтастық осы уақытқа дейін атақ үшін басым болды. Бұл ереже бойынша кім мұрагерлік ететіні белгісіз, бірақ, негізге сүйене отырып, талап қоюшы болмады. (Уильям Тыныштың екі үлкен қызы, олардың біреуі үйленген Уильям Луи, Нассау-Дилленбург графы, Джон Уильям Фризоның атасының ағасы, еш қиындықсыз қайтыс болды).

Алайда, Филипп Уильям, апельсин ханзадасы Уильям Тыныштың үлкен ұлы Рененің күш-жігерін жойып, агнатикалық сабақтастықты қалпына келтіріп, оны ерлер қатарына берді Джон VI, Нассау-Дилленбург графы, Уильям Тыныштың ағасы. Болғанындай, бұл ереженің бенефициары бір болды Уильям Гиацинт Нассау-Зиген туралы, ол 1702 жылы ерік-жігерге таласқан. Шатастыруды аяқтау үшін Морис, апельсин ханзадасы, Филипп Уильямның туған ағасы ерлер қатарына мұрагерлік беретін әсер қалдырды Эрнст Касимир - Нассау-Диц, Джон VI-ның кіші ұлы және Джон Уильям Фрисоның атасы. Бұл Джон Уильям Фрисо мұрагерлікке басты талап болды (Уильямның өсиетінің жанында). (Фредерик Генридің ерік-жігері оның туысқан ағасының бұл әрекетін бұзды, егер мұндай нәрсе мүмкін болар еді; Нассау-Дицтің өкілі Виллем Фредерик, кім басқаша пайда көрер еді).

Барлық осы шағымдар мен қарсы шағымдар, әсіресе, Пруссиялық Фредерик пен арасындағы күшті сот ісін жүргізуге негіз болды Henriëtte Amalia van Anhalt-Dessau, Джон Вилиам Фрисоның анасы, өйткені ол 1702 жылы әлі кәмелетке толмаған. Бұл сот ісі екі негізгі талап қоюшының ұрпағы арасында отыз жыл бойы жалғасуы керек еді, мәселе ақыр аяғында соттан тыс шешілгенге дейін. Бөлу туралы шарт арасында Уильям IV, апельсин ханзадасы, Джон Уильям Фризоның ұлы және Фредерик Уильям I Пруссиядан, Фредериктің ұлы, 1732 ж.. Соңғысы бұл арада Оранж княздігін берді Людовик XIV Франция құрамына кіретін келісімдердің бірімен Утрехт тыныштығы (Пруссияның аумақтық пайдасына айырбастау Жоғарғы гильдерлер[5]), осылайша титулға мұрагерлік мәселесі айтарлықтай маңызды емес (екі шағымданушы бұдан әрі бұл тақырыпты қолдануды шешті). Қалған мұра екі қарсыластың арасында бөлінді.[6]

Бұл оқиғаның импорты жас Джон Уильям Фрисоның апельсин князі атағына деген талаптары Уильям III қайтыс болғаннан кейін, шешуші жылдарда даулы болып, оны абырой мен күштің маңызды көзінен айырды. Ол Фризландия мен Гронингеннің жетекшісі болған, өйткені бұл кеңсе 1675 жылы мұрагерлікке айналған және ол әкесінің орнына келген Генри Касимир II, Нассау-Диц ханзадасы 1696 жылы, ол анасының регрессиясында болсын, өйткені ол кезде ол тоғызда ғана болатын. Ол енді Голландия мен Зеландиядағы кеңсені мұрагер болуға үміттенді, әсіресе Уильям III оны кеңсеге дайындап, оны өзінің саяси мұрагері еткендіктен және кеңсе мұрагерлікпен байланысты болды. Алайда, бұл ереже Уильям III-тің табиғи мұрагеріне байланысты болды. Голландиялық регенттер өсиеттік ережемен байланысты емес деп санайды.

Уильям қайтыс болғаннан кейін тоғыз күн өткенде Голландияның Ұлы зейнеткері, Антониа Гейнсиус, Генералды штаттардың алдына шығып, Голландия штаттары өз провинциясындағы стадтохердің бос орнына келмеуге шешім қабылдады деп мәлімдеді. 1650 жылғы желтоқсаннан бастап қала үкіметтеріне магистраттарды сайлау мәселелерінде стадтхолдер құқығын беретін ескі патенттер тағы да күшіне енді. Зеландия, Утрехт, Гелдерланд, Оверейссель, тіпті Дренте (әдетте Гронингеннен кейін стадиондар мәселесінде жүрді, бірақ 1696 жылы Вильгельм III тағайындады). The Regeringsreglementen 1675 ж. шығарылып, 1672 ж. дейінгі жағдай қалпына келтірілді.

Ескі мемлекеттер-партиялық фракциядан шыққан регенттер бұрынғы лауазымдарына қалпына келтірілді (яғни, көп жағдайда олардың отбасы мүшелері, өйткені ескі регенттер қайтыс болды) Уильям тағайындаған орангист регенттер есебінен. Бұл тазарту Голландияда бейбіт түрде өтті, бірақ Зеландияда және әсіресе Гелдерландта кейде ұзақ уақытқа созылған азаматтық толқулар болды, оны кейде милиция, тіпті федералды әскерлерді шақыру арқылы басуға тура келді. Гелдерландта бұл толқулардың артында шынымен де «демократиялық» импульс болды, өйткені олар жаңадан келуі керек еді ( жаңа плоои немесе «жаңа экипаж») Габсбургке дейінгі кеңестердің тексеруді талап еткен қарапайым адамдардың қолдауына ие болды. gemeensliedenжәне, әдетте, полиция және гильдия өкілдерінің, регентті қалалық үкіметтерде, бұл қатысушы мемлекеттер мен орангисттік регенттердің көңілінен шықты.[7]

Голландияға және басқа төрт провинцияға кез-келген бейімділік Фризоны стадтольдер етіп тағайындауы мүмкін болуы мүмкін, мүмкін халықаралық жағдайдың салдарынан болмады. Людовик XIV Франциямен жаңа қақтығыс басталғалы тұрды (Уильям III шынымен өмірінің соңғы күндерін дайындық жұмыстарын аяқтаумен өткізді) және он бес жасар баламен осындай маңызды кеңселерде тәжірибе жасауға уақыт болмады. стадтхолдер мен генерал-капитанның Голландия мемлекеттерінің армиясы. Сонымен қатар, генерал-штаттар Пруссиялық Фредерик I сияқты маңызды одақтасты ренжіткісі келмеді, ол 1702 жылы наурызда губернияларды басып алды. Линген және Мерс (бұл Уильямның патронатына жататын) және егер ол өзінің «заңды» мұрагерлікке ұмтылуына кедергі келтірсе, алдағы соғыста француз жағына өтіп кету қаупін төндірмейді.

Гейнсий және испан мұрагері соғысы

Антониа Гейнсиус 1689 жылдан бастап Ұлы зейнеткер болды, Уильям III Англия патшасы болған кезге дейін. Уильям өзінің жаңа тақырыптарын басқарумен айналысқан кезде (ол Англияны жаулап алудан гөрі оны жеңіп алудан гөрі оңайырақ екенін түсінді; сондықтан «жаулап алу» сөзі тыйым салынған, содан бері сол күйінде қалды) үйге бару үшін Нидерланд саясаткерлерін басқарудың бірдей қиын міндеті болды. Уильямның саясат үшін көптеген данышпандарымен бөліскен Гейнсийдің және оның көптеген қолдарының қолына берілді дипломатиялық сыйлықтар. Бұл дипломатиялық сыйлықтар сонымен қатар оны сақтау үшін қажет болды үлкен коалиция бірге Уильям Людовик XIV-ке қарсы құра алды Тоғыз жылдық соғыс. Оны патшаның соңғы өсиетінен кейін қайта тірілту керек болды Испаниялық Карл II, Испан тәжін Луидің немересіне қалдыру Филип Карлос 1700 жылы баласыз қайтыс болғаннан кейін, еуропалықтарға қауіп төндірді күш балансы (сондықтан еңбекпен әкелді Рисвик келісімі 1697 ж.) және бұл тепе-теңдікті сақтау жөніндегі дипломатиялық әрекеттер нәтижесіз аяқталды.

Уильям өзінің өмірінің соңғы жылын коалицияны қайта қалпына келтіруге жұмсады Австрия, оның немере ағасы Пруссиядан Фредерик I және көптеген неміс князьдері Испания тағына деген талапты қолдауға Карл III, Еуропаның қалған бөлігін басып қалуы мүмкін Испания мен Франция күштерінің одағын болдырмау құралы ретінде. Бұл әрекетке оған Гейнсиус көмек көрсетті (өйткені Республика Коалицияның негізін қалаған және одақтас әскерлердің үлкен контингентін ғана емес, сонымен қатар басқа одақтастарға олардың контингенттері үшін ақы төлеу үшін едәуір субсидиялар беруге шақырылатын еді) және оның ағылшын сүйікті герцогы Марлборо. Бұл дайындық келіссөздері Уильям 1702 жылы 19 наурызда аттан құлағаннан кейінгі асқынулардан қайтыс болған кезде аяқталды.

Уильямның күтпеген өлімі дайындықты тәртіпсіздікке ұшыратты. Тыныш төңкеріс, тұрақтылықты құлатып, Республикадағы Қатысушы-мемлекеттер режимін қайта енгізіп, Англиямен және басқа одақтастармен жарылыс тудырады ма? Бұған ешқашан қауіп төнген жоқ сияқты, егер Республика (қазіргі уақытта да ұлы держава болса) шет елдегі қайтыс болған стадтхолдер саясатымен, олар ойлауы мүмкін кез келген нәрсені бұзғысы келмегендіктен ғана. оның ішкі саясаты.

Сонымен қатар, Голландиялық регенттердің Коалицияға кірудің өзіндік себептері болды. 1701 жылы француз әскерлері кірді Оңтүстік Нидерланды испан билігінің келісімімен және голландтықтарды Рисвик бейбітшілігі кезінде алған тосқауыл бекіністерін эвакуациялауға мәжбүр етті. алдын алу мұндай француздық шабуыл. Бұл голландтықтар өздері мен француздар арасында артықшылық беретін аралық аймақты жойды. Бұдан да маңыздысы, француздар 1648 жылғы Испаниямен жасалған бітімгершілікке (Испания әрдайым мұқият қадағалап отырды) қарсы Антверпенмен сауда жасау үшін Шелдт ашты.[8]Сондай-ақ, Голландияның Испаниямен және Испания отарларымен сауда-саттығы Францияның меркантилистік саясатын ескере отырып, француз көпестеріне бағытталу қаупі бар сияқты болды. 1701 жылы Бурбонның жаңа королі Филипп V ауыстырды Асиенто мысалы, француз компаниясына, ал бұрын Dutch West India компаниясы іс жүзінде осы сауда концессиясына ие болды. Бір сөзбен айтқанда, голландтардың Луиске Испания мен оның иеліктерін иемденуіне қарсы тұрудың айқын стратегиялық себептерінен басқа көптеген экономикалық себептері болды.[9]

Алайда, Уильямның қайтыс болуы оның осы саладағы сөзсіз әскери көшбасшы ретіндегі жағдайы (тоғыз жылдық соғыс кезіндегідей) қазір бос тұру проблемасын тудырды. Алдымен ханшайым Аннаның князь-конторы ұсынылды Дания ханзадасы біріккен голланд және ағылшын армияларының «генералиссимусына» айналады, бірақ (бірақ олар ынта білдіргенімен) голландтар білікті генералға артықшылық беріп, Анл мен Джордждың сезімдерін қатты ренжітпестен Марлбороды алға итеріп жіберді. Марлбороды тағайындау лейтенант- Голландия армиясының генерал-капитанына (жоғарғы жұмысты ресми түрде бос қалдыру) қатысушы-мемлекеттер регенттері артықшылық берді, олар шетелдік генералға (саяси амбициясы жоқ) отандық генералға қарағанда көбірек сенді. 1650 жылдардағы алғашқы тұрақсыз кезеңде олар француз маршалын тағайындау идеясымен ойнады Туренна ештеңе шықпаса да.[10] Басқаша айтқанда, Марлбородың тағайындалуы олар үшін де саяси мәселені шешті. Сонымен қатар, құпия келісім бойынша, Марлборо даладағы жергілікті депутаттардың қамқорлығына алынды (бір түрі саяси комиссарлар ) оның шешімдеріне вето қою құқығымен. Бұл алдағы науқандарда үнемі үйкеліс көзі болатын еді, өйткені бұл саясаткерлер голландиялық әскерлердің Марлборо шешімдерінің стратегиялық жарқырауына байланысты тәуекелдерін атап өтуге бейім болды.[11]

Нидерландтардың бұл қызығушылығын (және Марлбородың осы тәрбиеге келісуі) одақтастардың ұрыс тәртібіндегі голландиялық әскер контингенттерінің басым рөлімен түсіндіруге болады. Нидерландтар Фландриядағы әскери театрға ағылшындардан шамамен екі есе көп әскер жіберді (1708 ж. 40 000-ға қарсы 100 000-нан астам), бұл ағылшын тарихнамасында қандай-да бір жағдайда жиі ескерусіз қалған және олар Пиреней театрында да маңызды рөл атқарған . Мысалы, Гибралтар біріккен ағылшын-голланд теңіз флотымен жаулап алынды және теңіз күші содан кейін Ұлыбритания 1713 жылы өзі үшін осы стратегиялық позицияны алғанға дейін бірлескен күшпен Чарльз III-нің атында болды.[12]

Голландия депутаттары мен генералдарымен болған келіспеушіліктерге қарамастан (олар әрдайым Марлбородың қабілеттеріне деген қорқынышты сезінбейтін) Генсиус пен Марлборо арасындағы келісімнің арқасында әскери-дипломатиялық саладағы ағылшын-голландиялық ынтымақтастық өте жақсы болды. Біріншісі қақтығыс кезінде Марлбороға қолдау көрсетті Генерал Слангенбург кейін Екерен шайқасы және Слангенбургтің Голландия қоғамдық пікіріндегі қаһармандық мәртебесіне қарамастан оны алып тастауға ықпал етті. Сияқты голланд генералдарымен ынтымақтастық Генри де Нассау, лорд Оверкирк шайқастарында Эликсхайм, Рамиллиес, және Оденард, кейінірек Джон Уильям Фрисомен бірге Malplaquet айтарлықтай жақсарды, сондай-ақ жергілікті голландиялық депутаттармен қарым-қатынас жақсарды Sicco van Goslinga.

Марлборо және Савой князі Евгений Осы саладағы жетістіктер нәтижесінде 1708 жылы Оңтүстік Нидерланды негізінен француз күштерінен тазартылды. Нидерландтардың экономикалық қызығушылығы басым болған осы елдің бірлескен ағылшын-голланд әскери оккупациясы құрылды. Нидерландтар Пиреней түбегіндегі одақтастардың операциялары Португалия мен Испанияда жүргізген ағылшын экономикалық басымдығы үшін ішінара өтемақы іздеді. Ұлыбритания үшін Португалия сияқты, Оңтүстік Голландия да жақында француздық меркантилистік шаралардың орнына 1680 жылғы қолайлы испандық тарифтер тізімін қалпына келтіру арқылы голландтар үшін тұтқын нарыққа айналды.[13]

Голландиялықтар сонымен қатар Оңтүстік Нидерландыдағы Габсбургтың болашақ бақылауын шектеп, Рисвик келісім-шартының тосқауыл ережелерінің жаңа жетілдірілген түрімен оны австриялық-голландиялық кодоминионға айналдыруға үміттенді. Гейнсиус енді Ұлыбританияға ұсыныс жасады 1707. Одақтың актілері ) Голландияның гарнизонға құқығын қайсысына болса да, және Генералды Штаттар қалаған Австрия Голландиясындағы сонша қалалар мен бекіністерге ағылшындардың қолдауымен айырбастау үшін протестанттық мұрагерліктің кепілі. Бұл кепілдіктермен алмасу (екі ел де өкінетін еді) әкелді Кедергі туралы келісім 1709 ж. сәйкес, Голландия Англияда тәртіп сақтау үшін 6000 әскер жіберуге мәжбүр болды Якубит 1715 жылдың көтерілуі және Якобит 1745 жылы көтерілді.[14]

1710 жылға қарай соғыс, одақтастардың осы жетістіктеріне қарамастан, тығырыққа тірелді. Француздар да, голландтар да таусылып, бейбітшілікке ұмтылды. Луис енді Голландия мұрындарының алдында оңтайлы жеке бейбітшілікке үміт артып, одақтастарды бөлуге әрекет жасады. 1710 жылдың көктеміндегі құпия емес Гертруйденберг келіссөздері кезінде Луи өзінің Филиппке өтемақы ретінде Италиядағы Габсбург территорияларын алу үшін немересі Филиппті Испания тағынан Чарльз III-нің пайдасына алуды ұсынды. Ол голландтарды Австрия Нидерландысындағы тосқауылмен және 1664 жылғы француздардың қолайлы тарифтік тізіміне қайта оралумен және басқа экономикалық жеңілдіктермен азғырды.

Нидерланд үкіметі қатты азғыруға ұшырады, бірақ күрделі себептерден бас тартты. Мұндай бөлек бейбітшілік олардың көзқарасы бойынша абыройсыздыққа ие болып қана қоймай, сонымен бірге оларға британдықтар мен австриялықтардың тұрақты араздығын тудырады. Олар Людовиктердің азғыруына түсіп қалған соң, одақтастарымен достықты қалпына келтіру қаншалықты қиын болғанын есіне алды Неймегеннің тыныштығы 1678 жылы және достарын тастап кетті. Олар сондай-ақ Луис бұрын сөзін қаншалықты жиі бұзғанын есіне алды. Келісімшарт Луис басқа қарсыластарымен қарым-қатынас жасағаннан кейін голландтықтарға ауысады деп күткен. Егер бұл орын алса, олар дос болмас еді. Соңында, Луидің Филипті қызметінен кетіру туралы келісімін қабылдағанына қарамастан, ол мұндай қызметтен кетуге белсенді қатысудан бас тартты. Одақтастар мұны өздері жасауы керек еді. Гейнсий және оның әріптестері соғысты жалғастырудың басқа баламасын көрмеді.[15]

Утрехт бейбітшілігі және Екінші Ұлы ассамблея

Луи ақырында Голландияны Ұлы Одақтан босатуға тырысқан нәтижесіз әрекеттерінен шаршады және өзінің назарын Ұлыбританияға аударды. Онда үлкен саяси өзгерістер болғандығы оның назарынан тыс қалмады. Алайда Анна ханшайым Уильям III-тен гөрі аз болды Виглер, ол көп ұзамай тек өзінің қолдауымен басқара алмайтынын білді Тарих және Тори үкіметімен жүргізілген алғашқы тәжірибелерден бастап Уигтің қолдауымен қалыпты Тори үкіметі болды Сидни Годольфин, Годольфиннің 1 графы және вигтерге сүйенетін Марлборо. Алайда, Марлбородың әйелі Сара Черчилль, Марлборо герцогинясы ұзақ уақыт бойы Анна ханшайымның сүйіктісі болған, осылайша күйеуіне бейресми қуат базасын беріп, патшайыммен араздасып қалған Абигейл Машам, баронесса Машам, Оны патшайымның пайдасына ауыстырған Сараның кедей туысы. Осыдан кейін Сараның жұлдызы төмендеді және онымен бірге күйеуі де болды. Оның орнына жұлдыз Роберт Харли, Оксфорд графы және граф Мортимер (Абигаилдің немере ағасы) көтеріліске шықты, әсіресе 1710 жылы парламенттік сайлауда ториялар жеңіске жеткеннен кейін.

Харли жаңа үкімет құрды Генри Сент Джон, 1-ші висконт Болингброк Мемлекеттік хатшы ретінде және осы жаңа үкімет Людовик XIV-пен Ұлыбритания мен Франция арасында жеке бейбітшілік орнату үшін жасырын келіссөздер жүргізді. Бұл келіссөздер көп ұзамай сәттілікке қол жеткізді, өйткені Луис үлкен жеңілдіктер жасауға дайын болды (ол негізінен голландтарға ұсынған концессияларды ұсынды, және тағы басқалары, мысалы порт Дюнкерк және оның Ұлыбританияның жаңа үкіметі өзінің одақтастарының мүдделерін қандай да бір мағынада құрметтеуге мәжбүр болған жоқ.

Егер бұл одақтастарға деген сенімді бұзу жеткіліксіз болса, Ұлыбритания үкіметі одақтастардың соғыс қимылдарын белсенді түрде диверсиялауға кірісті. 1712 жылы мамырда Болингброк бұйырды Ормонде герцогы Марлбороды британдық күштердің генерал-капитаны етіп тағайындаған (бірақ Голландия күштері емес, өйткені Голландия үкіметі ханзада Евгенийге командалық құрамды ауыстырған)[16]) ұрыс қимылдарына одан әрі қатысудан бас тартуға құқылы. Болингброк француздарға бұл нұсқаулық туралы хабарлады, бірақ одақтастар туралы емес. Алайда, бұл Кеснойды қоршау кезінде француз қолбасшысы, Вилларлар қоршау күштері астында британдық күштерді байқаған, түсінікті Ормонде түсіндіруді талап етті. Содан кейін британдық генерал одақтастар лагерінен өз күштерін шығарып, тек британдық сарбаздармен бірге жүріп кетті (британдықтардың жалақысындағы жалдамалылар ашық түрде кетуге қатысудан бас тартты). Бір қызығы, француздар өздерін қатты сезінді, өйткені олар күткен еді барлық Ұлыбританиядағы күштер жоғалып кетеді, осылайша князь Евгенийдің күшін өлтіреді. Бұл француз-британ келісімінің маңызды элементі болды. Уәде етілгендей, Франция мұндай жағдайда Дюнкерктен бас тартуға мәжбүр бола ма?[17]

Уинстон Черчилль британдық сарбаздардың сезімдерін былайша сипаттайды:

Редукаттардың қайғы-қасіреті жиі сипатталған. Темір тәртіпті сақтай отырып, осы уақытқа дейін Еуропаның лагерьлерінде есімдері соншама құрметке ие болған ардагер полктар мен батальондар мүсіркеген көздерімен аттанды, ал ұзақ соғыстағы жолдастары оларға мылжыңмен қарады. Кемсітушілікке қарсы ең қатаң бұйрықтар берілді, бірақ тыныштық ешқандай қауіп төндірмеген британдық сарбаздардың жүректеріне салқын тиді. Бірақ олар шерудің соңына жеткенде және қатарлары бұзылғанда, кішіпейіл адамдар еркектердің мушкеттерін сындырып, шаштарын жыртып, патшайым мен министрлікке оларды сол сынаққа ұшырататын қорлық пен қарғыс айтқандарына куә болды.[18]

Қалған одақтастар да өздерін осылай сезінді, әсіресе одан кейін Денейн шайқасы Англия әскерлерінің кетуіне байланысты одақтас күштің әлсіреуі нәтижесінде Голландия мен Австрия әскерлерінің өмірін едәуір жоғалтқандықтан, Евгений ханзада оны жоғалтты. Болингброк жеңімпаз Вилларсты жарақатқа тіл тигізіп, жеңісімен құттықтады. Утрехттегі ресми бейбіт келіссөздер кезінде британдықтар мен француздардың жасырын келісім жасасқанын және олардың үмітсіздіктердің голландиялықтар мен австриялықтарды шарпығанын анықтады. Гаагада Ұлыбританияға қарсы бүліктер болды, тіпті төртінші ағылшын-голланд соғысы туралы, мұндай соғыс басталмас бұрын алпыс сегіз жыл бұрын да айтылды. Австрия мен Республика қысқа уақыт ішінде өз бетінше соғысты жалғастыруға тырысты, бірақ голландтар мен пруссиялықтар көп ұзамай бұл үмітсіз ізденіс деген қорытындыға келді. Тек австриялықтар соғысты.[19]

Демек, 1713 жылы 11 сәуірде Утрехт келісімі (1713) Франция мен одақтастардың көпшілігі қол қойды. Франция жеңілдіктердің көп бөлігін жасады, бірақ егер Харли-Болингброк үкіметі өз одақтастарына опасыздық жасамаса, ондай болмады. Ұлыбритания Испанияда (Гибралтар мен Миноркада) және Солтүстік Америкада территориялық жеңілдіктермен ең жақсы нәтижеге қол жеткізді, ал кірісті Асиенто енді британдық консорциумға кетті, ол бір ғасырға жуық құл саудасынан пайда табуға ниеттенді. Үлкен жеңіліске ұшыраған Чарльз III болды, ол бүкіл соғыс басталған испан тәжін алмады. Алайда, Чарльз бұл уақытта Қасиетті Рим Императорына айналды, бұл одақтастардың оның талаптарын қолдауға деген ынта-ықыласын бәсеңдетті. Бұл Еуропадағы күштер тепе-теңдігін Хабсбургке бейім жолмен өзгерткен болар еді. Алайда, өтемақы ретінде Австрия Италиядағы бұрынғы испандық иеліктерден басқа бұрынғы Испания Нидерландысын азды-көпті толық алды (Савойға барған, бірақ кейін Австриямен Сардинияға ауыстырылған Сицилиядан басқа).

Республиканың екінші болып үздік шыққандығы туралы көп нәрсе жасалғанымен (француз келіссөзшісінің мазақтары, Мельхиор де Полигнак, «De vous, chez vous, sans vous», демек, бейбітшілік конгресі өз елдеріндегі голландиялық мүдделерді шешті, бірақ оларсыз,[20] олар соғыс мақсаттарының көп бөлігіне қол жеткізді: Австрия Нидерланды бойынша қалаған кодоминионына және сол елдегі бекіністер тосқауылына 1715 жылғы қараша айындағы Австрия-Нидерланд шарты бойынша қол жеткізілді (Франция Утрехтте онсыз да мойындаған) , дегенмен, голландтар, британдықтардың кедергісі салдарынан, олар ойлағанның бәрін ала алмады.[21]

Рисвик келісімі қайта бекітілді (шын мәнінде, Утрехт келісімінің франко-голланд бөлігі сол шартпен синоним болып табылады; тек преамбулалар ғана ерекшеленеді) және бұл француздардың маңызды экономикалық жеңілдіктерін, әсіресе елге қайта оралуын көздеді. French tariff list of 1664. Important in the economic field was also that the closing of the Scheldt to trade with Antwerp was once again confirmed.

Still, disillusionment in government circles of the Republic was great. Heinsius policy of alliance with Great Britain was in ruins, which he personally took very hard. It has been said that he was a broken man afterwards and never regained his prestige and influence, even though he remained in office as Grand Pensionary until his death in 1720. Relations with Great Britain were very strained as long as the Harley-Bolingbroke ministry remained in office. This was only for a short time, however, as they fell in disfavor after the death of Queen Anne and the accession to the British throne of the Elector of Hanover, Джордж I Ұлыбритания in August, 1714. Both were impeached and Bolingbroke would spend the remainder of his life in exile in France. The new king greatly preferred the Whigs and in the new Ministry Marlborough returned to power. The Republic and Great Britain now entered on a long-lasting period of amity, which would last as long as the Whigs were in power.

The policy of working in tandem between the Republic and Great Britain was definitively a thing of the past, however. The Dutch had lost their trust in the British. The Republic now embarked on a policy of Neutralism, which would last until the end of the stadtholderless period. To put it differently: the Republic resigned voluntarily as a Great Power. As soon as the peace was signed the States General started disbanding the Dutch army. Troop strength was reduced from 130,000 in 1713 to 40,000 (about the pre-1672 strength) in 1715. The reductions in the navy were comparable. This was a decisive change, because other European powers kept their armies and navies up to strength.[22]

The main reason for this voluntary resignation, so to speak, was the dire situation of the finances of the Republic. The Dutch had financed the wars of William III primarily with borrowing. Consequently, the public debt had risen from 38 million guilders after the end of the Franco-Dutch war in 1678 to the staggering sum of 128 million guilders in 1713. In itself this need not be debilitating, but the debt-service of this tremendous debt consumed almost all of the normal tax revenue. Something evidently had to give. The tax burden was already appreciable and the government felt that could not be increased. The only feasible alternative seemed to be reductions in expenditures, and as most government expenditures were in the military sphere, that is where they had to be made.[23]

However, there was another possibility, at least in theory, to get out from under the debt burden and retain the Republic's military stature: fiscal reform. The quota system which determined the contributions of the seven provinces to the communal budget had not been revised since 1616 and had arguably grown skewed. But this was just one symptom of the debilitating particularism of the government of the Republic. The secretary of the Раад ван штаты (Мемлекеттік кеңес) Саймон ван Слингландт privately enumerated a number of necessary constitutional reforms in his Political Discourses[24](which would only be published posthumously in 1785) and he set to work in an effort to implement them.[25]

On the initiative of the States of Overijssel the States-General were convened in a number of extraordinary sessions, collectively known as the Tweede Grote Vergadering (Second Great Assembly, a kind of Конституциялық конвенция ) of the years 1716-7 to discuss his proposals. The term was chosen as a reminder of the Great Assembly of 1651 which inaugurated the first stadtholderless period. But that first Great Assembly had been a special congress of the provincial States, whereas in this case only the States General were involved. Nevertheless, the term is appropriate, because no less than a revision of the Утрехт одағы -treaty was intended.[23]

As secretary of the Раад ван штаты (a federal institution) Van Slingelandt was able to take a federal perspective, as opposed to a purely provincial perspective, as most other politicians (even the Grand Pensionary) were wont to do. One of the criticisms Van Slingelandt made, was that unlike in the early years of the Republic (which he held up as a positive example) majority-voting was far less common, leading to debilitating deadlock in the decisionmaking. As a matter of fact, one of the arguments of the defenders of the stadtholderate was that article 7 of the Union of Utrecht had charged the stadtholders of the several provinces (there was still supposed to be more than one at that time) with breaking such deadlocks in the States-General through arbitration. Van Slingelandt, however (not surprisingly in view of his position in the Раад ван штаты), proposed a different solution to the problem of particularism: he wished to revert to a stronger position of the Раад as an executive organ for the Republic, as had arguably existed before the inclusion of two English members in that council under the governorate-general of the Лестер графы in 1586 (which membership lasted until 1625) necessitated the emasculation of that council by Йохан ван Олденбарнвельт. A strong executive (but not an "eminent head", the alternative the Orangists always preferred) would in his view bring about the other reforms necessary to reform the public finances, that in turn would bring about the restoration of the Republic as a leading military and diplomatic power. (And this in turn would enable the Republic to reverse the trend among its neighbors to put protectionist measures in the path of Dutch trade and industry, which already were beginning to cause the steep decline of the Dutch economy in these years. The Republic had previously been able to counter such measures by diplomatic, even military, means.) Unfortunately, vested interests were too strong, and despite much debate the Great Assembly came to nothing.[26]

The Van Hoornbeek and Van Slingelandt terms in office

Apparently, Van Slingelandt's efforts at reform not only failed, but he had made so many enemies trying to implement them, that his career was interrupted. When Heinsius died in August, 1720 Van Slingelandt was pointedly passed over for the office of Grand Pensionary and it was given to Исаак ван Хорнбик. Van Hoornbeek had been зейнеткер of the city of Rotterdam and as such he represented that city in the States-General. During Heinsius' term in office he often assisted the Grand Pensionary in a diplomatic capacity and in managing the political troubles between the provinces. He was, however, more a civil servant, than a politician by temperament. This militated against his taking a role as a forceful political leader, as other Grand Pensionaries, like Johan de Witt, and to a lesser extent, Gaspar Fagel and Heinsius had been.

This is probably just the way his backers liked it. Neutralist sentiment was still strong in the years following the Barrier Treaty with Austria of 1715. The Republic felt safe from French incursions behind the string of fortresses in the Austrian Netherlands it was now allowed to garrison. Besides, under the Regency of Филипп II, Орлеан герцогы after the death of Louis XIV, France hardly formed a menace. Though the States-General viewed the acquisitive policies of Фредерик Уильям I Пруссиядан on the eastern frontier of the Republic with some trepidation this as yet did not form a reason to seek safety in defensive alliances. Nevertheless, other European powers did not necessarily accept such an aloof posture (used as they were to the hyperactivity in the first decade of the century), and the Republic was pressured to become part of the Quadruple Alliance and take part in its Испанияға қарсы соғыс after 1718. However, though the Republic formally acceded to the Alliance, obstruction of the city of Amsterdam, which feared for its trade interests in Spain and its colonies, prevented an active part of the Dutch military (though the Republic's diplomats hosted the peace negotiations that ended the war).[27]

On the internal political front all had been quiet since the premature death of John William Friso in 1711. He had a posthumous son, Уильям IV, апельсин ханзадасы, who was born about six weeks after his death. That infant was no serious candidate for any official post in the Republic, though the Frisian States faithfully promised to appoint him to their stadtholdership, once he would come of age. In the meantime his mother Marie Louise of Hesse-Kassel (like her mother-in-law before her) acted as regent for him in Friesland, and pursued the litigation over the inheritance of William III with Frederick William of Prussia.

But Orangism as a political force remained dormant until in 1718 the States of Friesland formally designated him their future stadtholder, followed the next year by the States of Groningen. In 1722 the States of Drenthe followed suit, but what made the other provinces suspicious was that the same year Orangists in the States of Gelderland started agitating to make him prospective stadtholder there too. This was a new development, as stadtholders of the House of Nassau-Dietz previously had only served in the three northern provinces mentioned just now. Holland, Zeeland and Overijssel therefore tried to intervene, but the Gelderland Orangists prevailed, though the States of Gelderland at the same time drew up an Instructie (commission) that almost reduced his powers to nothing, certainly compared to the authority William III had possessed under the Government Regulations of 1675. Nevertheless, this decision of Gelderland caused a backlash in the other stadtholderless provinces that reaffirmed their firm rejection of a new stadtholderate in 1723.[28]

When Van Hoornbeek died in office in 1727 Van Slingelandt finally got his chance as Grand Pensionary, though his suspected Orangist leanings caused his principals to demand a verbal promise that he would maintain the stadtholderless regime. He also had to promise that he would not try again to bring about constitutional reforms.[29]

William IV came of age in 1729 and was duly appointed stadtholder in Friesland, Groningen, Drenthe and Gelderland. Holland barred him immediately from the Раад ван штаты (and also of the captaincy-general of the Union) on the pretext that his appointment would give the northern provinces an undue advantage. In 1732 he concluded the Treaty of Partition over the contested inheritance of the Prince of Orange with his rival Frederick William. By the terms of the treaty, William and Frederick William agreed to recognize each other as Princes of Orange. William also got the right to refer to his House as Orange-Nassau. As a result of the treaty, William's political position improved appreciably. It now looked as if the mighty Prussian king would start supporting him in the politics of the Republic.

One consequence of the settlement was that the Prussian king removed his objections to the assumption by William IV of the dignity of First Noble in the States of Zeeland, on the basis of his ownership of the Marquisates of Veere and Vlissingen. To block such a move the States of Zeeland (who did not want him in their midst) first offered to buy the two marquisates, and when he refused, compulsorily bought them, depositing the purchase price in an escrow account.[30]

On a different front the young stadtholder improved his position through a marriage alliance with the British royal house of Hanover. Ұлыбританияның Джордж II was not very secure in his hold on his throne and hoped to strengthen it by offering his daughter Энн in marriage to what he mistook for an influential politician of the Republic, with which, after all old ties existed, reaching back to the Glorious Revolution. At first Van Slingelandt reacted negatively to the proposal with such vehemence that the project was held in abeyance for a few years, but eventually he ran out of excuses and William and Anne were married at St. James's Palace in London in March, 1734. The States-General were barely polite, merely congratulating the king on selecting a son-in-law from "a free republic such as ours.[31]" The poor princess, used to a proper royal court, was buried for the next thirteen years in the provincial mediocrity of the stadtholder's court in Люварден.

Nevertheless, the royal marriage was an indication that the Republic was at least still perceived in European capitals as a power that was worth wooing for the other powers. Despite its neutralist preferences the Republic had been dragged into the Alliance of Hanover of 1725. Though this alliance was formally intended to counter the alliance between Austria and Spain, the Republic hoped it would be a vehicle to manage the king of Prussia, who was trying to get his hands on the Duchy of Jülich that abutted Dutch territory, and threatened to engulf Dutch Generality Lands in Prussian territory.[32]

These are just examples of the intricate minuets European diplomats danced in this first third of the 18th century and in which Van Slingelandt tried his best to be the dance master. The Republic almost got involved in the Поляк мұрагері соғысы, to such an extent that it was forced to increase its army just at the time it had hoped to be able to reduce it appreciably. Van Slingelandt played an important part as an intermediary in bringing about peace in that conflict between the Bourbon and Habsburg powers in 1735.[33]

Decline of the Republic

The political history of the Republic after the Peace of Utrecht, but before the upheavals of the 1740s, is characterized by a certain blandness (not only in the Republic, to be sure; the contemporary long-lasting Ministry of Роберт Уалпол in Great Britain equally elicits little passion). In Dutch historiography the sobriquet Pruikentijd (перивиг era) is often used, in a scornful way. This is because one associates it with the long decline of the Republic in the political, diplomatic and military fields, that may have started earlier, but became manifest toward the middle of the century. The main cause of this decline lay, however, in the economic field.

The Republic became a Great Power in the middle of the 17th century because of the primacy of its trading system. The riches its merchants, bankers and industrialists accumulated enabled the Dutch state to erect a system of public finance that was unsurpassed for early modern Europe. That system enabled it to finance a military apparatus that was the equal of those of far larger contemporary European powers, and thus to hold its own in the great conflicts around the turn of the 18th century. The limits of this system were however reached at the end of the War of Spanish Succession, and the Republic was financially exhausted, just like France.

However, unlike France, the Republic was unable to restore its finances in the next decades and the reason for this inability was that the health of the underlying economy had already started to decline. The cause of this was a complex of factors. First and foremost, the "industrial revolution" that had been the basis of Dutch prosperity in the Golden Age, went into reverse. Because of the reversal of the secular trend of European price levels around 1670 (secular inflation turning into deflation) and the downward-stickiness of nominal wages, Dutch real wages (already high in boom times) became prohibitively high for the Dutch export industries, making Dutch industrial products uncompetitive. This competitive disadvantage was magnified by the protectionist measures that first France, and after 1720 also Prussia, the Scandinavian countries, and Russia took to keep Dutch industrial export products out. Dutch export industries were therefore deprived of their major markets and withered at the vine.[34]

The contrast with Great Britain, that was confronted with similar challenges at the time, is instructive. English industry would have become equally uncompetitive, but it was able to compensate for the loss of markets in Europe, by its grip on captive markets in its American colonies, and in the markets in Portugal, Spain, and the Spanish colonial empire it had gained (replacing the Dutch) as a consequence of the Peace of Utrecht. This is where the British really gained, and the Dutch really lost, from that peculiar peace deal. The Republic lacked the imperial power, large navy,[35] and populous colonies that Great Britain used to sustain its economic growth.[34]

The decline in Dutch exports (especially textiles) caused a decline in the "rich" trades also, because after all, trade is always two-sided. The Republic could not just offer bullion, as Spain had been able to do in its heyday, to pay for its imports. It is true that the other mainstay of Dutch trade: the carrying trade in which the Republic offered shipping services, for a long time remained important. The fact that the Republic was able to remain neutral in most wars that Great Britain fought, and that Dutch shipping enjoyed immunity from English inspection for contraband, due to the Бреда келісімі (1667) (confirmed at the Вестминстер келісімі (1674) ), certainly gave Dutch shipping a competitive advantage above its less fortunate competitors, added to the already greater efficiency that Dutch ships enjoyed. (The principle of "free ship, free goods" made Dutch shippers the carriers-of-choice for belligerent and neutral alike, to avoid confiscations by the British navy). But these shipping services did not have an added value comparable to that of the "rich trades." In any case, though the volume of the Dutch Baltic trade remained constant, the volume of that of other countries grew. The Dutch Baltic trade declined therefore салыстырмалы түрде.[34]

During the first half of the 18th century the "rich trades" from Asia, in which the VOC played a preponderant role, still remained strong, but here also superficial flowering was deceptive. The problem was low profitability. The VOC for a while dominated the Малабар және Коромандель coasts in India, successfully keeping its English, French, and Danish competitors at bay, but by 1720 it became clear that the financial outlay for the military presence it had to maintain, outweighed the profits. The VOC therefore quietly decided to abandon India to its competitors. Likewise, though the VOC followed the example of its competitors in changing its "business model" in favor of wholesale trade in textiles, Чинавар, tea and coffee, from the old emphasis of the high-profit spices (in which it had a near-monopoly), and grew to double its old size, becoming the largest company in the world, this was mainly "profitless growth."

Ironically, this relative decline of the Dutch economy through increased competition from abroad was partly due to the behavior of Dutch capitalists. The Dutch economy had grown explosively in the 17th century because of retention and reinvestment of profits. Capital begat capital. However, the fastly accumulating fund of Dutch capital had to be profitably reinvested. Because of the structural changes in the economic situation investment opportunities in the Dutch economy became scarcer just at the time when the perceived risk of investing in more lucrative ventures abroad became smaller. Dutch capitalists therefore started on a large тікелей шетелдік инвестициялар boom, especially in Great Britain, where the "Dutch" innovations in the capital market (e.g. the funded public debt) after the founding of the Англия банкі in 1696 had promoted the interconnection of the capital markets of both countries. Ironically, Dutch investors now helped finance the EIC, the Bank of England itself, and many other English economic ventures that helped to bring about rapid economic growth in England at the same time that growth in the Republic came to a standstill.[36]

This continued accumulation of capital mostly accrued to a small capitalist elite that slowly acquired the characteristics of a рентье -сынып. This type of investor was risk-averse and therefore preferred investment in liquid, financial assets like government bonds (foreign or domestic) over productive investments like shipping, mercantile inventory, industrial stock or agricultural land, like its ancestors had held. They literally had a vested interest in the funded public debt of the Dutch state, and as this elite was largely the same as the political elite (both Orangist and States Party) their political actions were often designed to protect that interest.[37] Unlike in other nation states in financial difficulty, defaulting on the debt, or diluting its value by inflation, would be unthinkable; the Dutch state fought for its public credit to the bitter end. At the same time, anything that would threaten that credit was anathema to this elite. Hence the wish of the government to avoid policies that would threaten its ability to service the debt, and its extreme parsimony in public expenditures after 1713 (which probably had a negative Keynesian effect on the economy also).

Of course, the economic decline eroded the revenue base on which the debt service depended. This was the main constraint on deficit spending, not the lending capacity of Dutch capitalists. Indeed, in later emergencies the Republic had no difficulty in doubling, even redoubling the public debt, but because of the increased debt service this entailed, such expansions of the public debt made the tax burden unbearable in the public's view. That tax burden was borne unequally by the several strata of Dutch society, as it was heavily skewed toward excises and other indirect taxes, whereas wealth, income and commerce were as yet lightly taxed, if at all. The result was that the middle strata of society were severely squeezed in the declining economic situation, characterized by increasing poverty of the lower strata. And the regents were well aware of this, which increased their reluctance to augment the tax burden, so as to avoid public discontent getting out of hand. A forlorn hope, as we will see.[38]

The States-Party regime therefore earnestly attempted to keep expenditure low. And as we have seen, this meant primarily economizing on military expenditures, as these comprised the bulk of the federal budget. The consequence was what amounted to unilateral disarmament (though fortunately this was only dimly perceived by predatory foreign powers, who for a long time remained duly deterred by the fierce reputation the Republic had acquired under the stadtholderate of William III). Disarmament necessitated a modest posture in foreign affairs exactly at the time that foreign protectionist policies might have necessitated diplomatic countermeasures, backed by military might (as the Republic had practiced against Scandinavian powers during the first stadtholderless period). Of course, the Republic could have retaliated peacefully (as it did in 1671, when it countered France's Colbert tariff list, with equally draconian tariffs on French wine), but because the position of the Dutch entrepot (which gave it a stranglehold on the French wine trade in 1671) had declined appreciably also, this kind of retaliation would be self-defeating. Equally, protectionist measures like Prussia's banning of all textile imports in the early 1720s (to protect its own infant textile industry) could not profitably be emulated by the Dutch government, because the Dutch industry was already mature and did not need protection; it needed foreign markets, because the Dutch home market was too small for it to be profitable.

All of this goes to show that (also in hindsight) it is not realistic to blame the States-Party regime for the economic malaise. Even if they had been aware of the underlying economic processes (and this is doubtful, though some contemporaries were, like Исаак де Пинто in his later published Traité de la Circulation et du Crédit[34]) it is not clear what they could have done about it, as far as the economy as a whole is concerned, though they could arguably have reformed the public finances. As it was, only a feeble attempt to restructure the real estate tax (verponding) was made by Van Slingelandt, and later an attempt to introduce a primitive form of income tax (the Personeel Quotisatie of 1742).[39]

The economic decline caused appalling phenomena, like the accelerating индустрияландыру after the early 1720s. Because less replacement and new merchant vessels were required with a declining trade level, the timber trade and shipbuilding industry of the Заан district went into a disastrous slump, the number of shipyards declining from over forty in 1690 to twenty-three in 1750.The linen-weaving industry was decimated in Twenthe and other inland areas, as was the whale oil, sail-canvas and rope-making industry in the Zaan. And these are only a few examples.[40] And deindustrialization brought deurbanization with it, as the job losses drove the urban population to rural areas where they still could earn a living. As a consequence, uniquely in early-18th-century Europe, Dutch cities shrunk in size, where everywhere else countries became more urbanized, and cities grew.[41]

Of course these negative economic and social developments had their influence on popular opinion and caused rising political discontent with the stadtholderless regime. It may be that (as Dutch historians like L.J. Rogier have argued[42]) there had been a marked deterioration in the quality of regent government, with a noticeable increase in corruption and nepotism (though coryphaei of the stadtholderate eras like Корнелис Муш, Johan Kievit және Johan van Banchem had been symptomatic of the same endemic sickness during the heyday of the Stadtholderate), though people were more tolerant of this than nowadays. It certainly was true that the governing institutions of the Republic were perennially deadlocked, and the Republic had become notorious for its indecisiveness (though, again this might be exaggerated). Though blaming the regents for the economic әлсіздік would be equally unjust as blaming the Chinese emperors for losing the favor of Heaven, the Dutch popular masses were equally capable of such a harsh judgment as the Chinese ones.

What remained for the apologists of the regime to defend it from the Orangist attacks was the claim that it promoted "freedom" in the sense of the "True Freedom" of the De Witt regime from the previous stadtholderless regime, with all that comprised: religious and intellectual toleration, and the principle that power is more responsibly wielded, and exercised in the public interest, if it is dispersed, with the dynastic element, embodied in the stadtholderate, removed. The fervently anti-Orangist regent Levinus Ferdinand de Beaufort added a third element: that the regime upheld civil freedom and the dignity of the individual, in his Verhandeling van de vryheit in den Burgerstaet (Treatise about freedom in the Civilian State; 1737). This became the centerpiece of a broad public polemic between Orangists and anti-Orangists about the ideological foundation of the alternative regimes, which was not without importance for the underpinning of the liberal revolutions later in the century. In it the defenders of the stadtholderless regime reminded their readers that the stadtholders had always acted like enemies of the "true freedom" of the Republic, and that William III had usurped an unacceptable amount of power.[43] Tragically, these warnings would be ignored in the crisis that ended the regime in the next decade.

Crisis and the Orangist revolution of 1747

Van Slingelandt was succeeded after his death in office in 1736 by Anthonie van der Heim as Grand Pensionary, be it after a protracted power struggle. He had to promise in writing that he would oppose the resurrection of the stadtholderate. He was a compromise candidate, maintaining good relations with all factions, even the Orangists. He was a competent administrator, but of necessity a colourless personage, of whom it would have been unreasonable to expect strong leadership.[44]

During his term in office the Republic slowly drifted into the Австрия мұрагері соғысы, which had started as a Prusso-Austrian conflict, but in which eventually all the neighbors of the Republic became involved: Prussia and France, and their allies on one side, and Austria and Great Britain (after 1744) and their allies on the other. At first the Republic strove mightily to remain neutral in this European conflict. Unfortunately, the fact that it maintained garrisons in a number of fortresses in the Austrian Netherlands implied that it implicitly defended that country against France (though that was not the Republic's intent). At times the number of Dutch troops in the Austrian Netherlands was larger than the Austrian contingent. This enabled the Austrians to fight with increased strength elsewhere. The French had an understandable grievance and made threatening noises. This spurred the Republic to bring its army finally again up to European standards (84,000 men in 1743).[45]

In 1744 the French made their first move against the Dutch at the barrier fortress of Менен, which surrendered after a token resistance of a week. Encouraged by this success the French next invested Турнир, another Dutch barrier fortress. This prompted the Republic to join the Төрттік Альянс of 1745 and the relieving army under Ханзада Уильям, Камберленд герцогы. This met a severe defeat at the hands of French Marshal Морис де Сакс кезінде Фонтеной шайқасы in May, 1745. The Austrian Netherlands now lay open for the French, especially as the Якобит 1745 жылы көтерілді opened a second front in the British homeland, which necessitated the urgent recall of Cumberland with most of his troops, soon followed by an expeditionary force of 6,000 Dutch troops (which could be hardly spared), which the Dutch owed due to their guarantee of the Hanoverian regime in Great Britain. During 1746 the French occupied most big cities in the Austrian Netherlands. Then, in April 1747, apparently as an exercise in armed diplomacy, a relatively small French army occupied Фландрия штаттары.[46]

This relatively innocuous invasion fully exposed the rottenness of the Dutch defenses, as if the French had driven a pen knife into a rotting windowsill. The consequences were spectacular. The Dutch population, still mindful of the French invasion in the Year of Disaster of 1672, went into a state of blind panic (though the actual situation was far from desperate as it had been in that year). As in 1672 the people started clamoring for a restoration of the stadtholderate.[46] This did not necessarily improve matters militarily. William IV, who had been waiting in the wings impatiently since he got his vaunted title of Prince of Orange back in 1732, was no great military genius, as he proved at the Лауфельд шайқасы, where he led the Dutch contingent shortly after his elevation in May, 1747 to stadtholder in all provinces, and to captain-general of the Union. The war itself was brought to a not-too-devastating end for the Republic with the Экс-ла-Шапель келісімі (1748), and the French retreated of their own accord from the Dutch frontier.

The popular revolution of April, 1747, started (understandably, in view of the nearness of the French invaders) in Zeeland, where the States post-haste restored William's position as First Noble in the States (and the marquisates they had compulsorily bought in 1732). The restoration of the stadtholderate was proclaimed (under pressure of rioting at Middelburg and Zierikzee) on April 28.[47]

Then the unrest spread to Holland. The city of Rotterdam was soon engulfed in orange banners and cockades and the vroedschap was forced to propose the restoration of the stadtholderate in Holland, too. Huge demonstrations of Orangist adherents followed in The Hague, Dordrecht and other cities in Holland. The Holland States begged the Prince's representatives, Виллем Бентинк ван Рун, a son of William III's faithful retainer Уильям Бентинк, 1-ші Портланд графы, және Willem van Haren, grietman туралы Хет Билдт to calm the mob that was milling outside their windows. People started wearing orange. In Amsterdam "a number of Republicans and Catholics, who refused to wear orange emblems, were thrown in the canals.[48]"

Holland proclaimed the restoration of the stadtholderate and the appointment of William IV to it on May 3. Utrecht and Overijssel followed by mid-May. All seven provinces (plus Drenthe) now recognized William IV as stadtholder, technically ending the second stadtholderless period. But the stadtholderless regime was still in place. The people started to express their fury at the representatives of this regime, and incidentally at Catholics, whose toleration apparently still enraged the Calvinist followers of the Orangist ideology (just as the revolution of 1672 had been accompanied by agitation against minority Protestant sects). Just like in 1672 this new popular revolt had democratic overtones also: people demanded popular involvement in civic government, reforms to curb corruption and financial abuses, a programme to revive commerce and industry, and (peculiarly in modern eyes) stricter curbs on swearing in public and desecrating the sabbath.[49]

At first William, satisfied with his political gains, did nothing to accede to these demands. Bentinck (who had a keen political mind) saw farther and advised the purge of the leaders of the States Party: Grand Pensionary Jacob Gilles (who had succeeded Van der Heim in 1746), secretary of the raad van state Adriaen van der Hoop, and sundry regents and the leaders of the ridderschappen in Holland and Overijssel. Except for Van der Hoop, for the moment nobody was removed, however. But the anti-Catholic riots continued, keeping unrest at a fever pitch. Soon this unrest was redirected in a more political direction by agitators like Daniel Raap. These started to support Bentinck's demands for the dismissal of the States-Party regents. But still William did nothing. Bentinck started to fear that this inaction would disaffect the popular masses and undermine support for the stadtholderate.[50]

Nevertheless, William, and his wife Princess Anne, were not unappreciative of the popular support for the Orangist cause. He reckoned that mob rule would cow the regents and make them suitably pliable to his demands. The advantages of this were demonstrated when in November, 1747, the city of Amsterdam alone opposed making the stadtholderate hereditary in both the male and female lines of William IV (who had only a daughter at the time). Raap, and another agitator, Жан Рузет де Мисси, now orchestrated more mob violence in Amsterdam in support of the proposal, which duly passed.[51]

In May 1747 the States of Utrecht were compelled to readopt the Government Regulations of 1675, which had given William III such a tight grip on the province. Gelderland and Overijssel soon had to follow, egged on by mob violence. Even Groningen and Friesland, William's "own" provinces, who had traditionally allowed their stadtholder very limited powers, were put under pressure to give him greatly extended prerogatives. Mob violence broke out in Groningen in March 1748. William refused to send federal troops to restore order. Only then did the Groningen States make far-reaching concessions that gave William powers comparable to those in Utrecht, Overijssel and Gelderland. Equally, after mob violence in May 1748 in Friesland the States were forced to request a Government Regulation on the model of the Utrecht one, depriving them of their ancient privileges.[52]

The unrest in Friesland was the first to exhibit a new phase in the revolution. There not only the regents were attacked but also the салық фермерлері. The Republic had long used tax farming, because of its convenience. The revenue of excises and other transaction taxes was uncertain, as it was dependent on the phase of the business cycle. The city governments (who were mainly responsible for tax gathering) therefore preferred to auction off the right to gather certain taxes to entrepreneurs for fixed periods. The entrepreneur paid a lump sum in advance and tried to recoup his outlay from the citizens who were liable for the tax, hoping to pocket the surplus of the actual tax revenue over the lump sum. Such a surplus was inherent in the system and did not represent an abuse in itself. However, abuses in actual tax administration were often unavoidable and caused widespread discontent. The tax riots in Friesland soon spread to Holland. Houses of tax farmers were ransacked in Haarlem, Leiden, The Hague, and especially Amsterdam. The riots became known as the Pachtersoproer. The civic militia refused to intervene, but used the riots as an occasion to present their own political demands: the right of the militia to elect their own officers; the right of the people to inspect tax registers; publication of civil rights so that people would know what they were; restoration of the rights of the guilds; enforcement of the laws respecting the sabbath; and preference for followers of Gisbertus Voetius as preachers in the public church. Soon thereafter the tax farms were abolished, though the other demands remained in abeyance.[53]

There now appeared to be two streams of protest going on. On the one hand Orangist agitators, orchestrated by Bentinck and the stadtholder's court, continued to demand саяси концессиялар from the regents by judicially withholding troops to restore order, until their demands were met. On the other hand, there were more ideologically inspired agitators, like Rousset de Missy and Elie Luzac, who (quoting Джон Локк Келіңіздер Үкімет туралы екі трактат) tried to introduce "dangerous ideas", like the ultimate sovereignty of the people as a justification for enlisting the support of the people.[54] Such ideas (anathema to both the clique around the stadtholder and the old States Party regents) were Vogue with a broad popular movement under the middle strata of the population, that aimed to make the government answerable to the people. This movement, known as the Doelisten (because they often congregated in the target ranges of the civic militia, which in Dutch were called the doelen) presented demands to the Amsterdam vroedschap in the summer of 1748 that the burgomasters should henceforth be made popularly electable, as also the directors of the Amsterdam Chamber of the VOC.[55]

This more radical wing more and more came into conflict with the moderates around Bentinck and the stadtholder himself. The States of Holland, now thoroughly alarmed by these "radical" developments, asked the stadtholder to go to Amsterdam in person to restore order by whatever means necessary. When the Prince visited the city on this mision in September 1748 he talked to representatives of both wings of the Doelisten. He was reluctant to accede to the demands of the radicals that the Amsterdam vroedschap should be purged, though he had to change his mind under pressure of huge demonstrations favoring the radicals. The purge fell, however, far short of what the radicals had hoped for. Жаңа vroedschap still contained many members of the old regent families. The Prince refused to accede to further demands, leaving the Amsterdam populace distinctly disaffected. This was the first clear break between the new regime and a large part of its popular following.[56]

Similar developments ensued in other Holland cities: William's purges of the city governments in response to popular demand were halfhearted and fell short of expectations, causing further disaffection. William was ready to promote change, but only as far as it suited him. He continued to promote the introduction of government regulations, like those of the inland provinces, in Holland also. These were intended to give him a firm grip on government patronage, so as to entrench his loyal placements in all strategic government positions. Eventually he managed to achieve this aim in all provinces. Бентинк сияқты адамдар билік тізгінін жалғыз «көрнекті бастың» қолына жинау көп ұзамай Голландия экономикасы мен қаржысының жағдайын қалпына келтіруге көмектеседі деп үміттенді. «Ағартылған деспотқа» деген осындай үлкен үміттер сол кезде тек Республикаға ғана тән емес еді. Португалияда адамдар бірдей үміт күтті Себастьяо Хосе де Карвальо және Мело, Помбалдың Маркизасы және патша Португалиядағы Джозеф I Швециядағы адамдар сияқты Швециядан Густав III.

Уильям IV мұндай үміттерді ақтай алар ма еді, біз, өкінішке орай, оны ешқашан білмейміз, өйткені ол 1751 жылы 22 қазанда 40 жасында кенеттен қайтыс болды.[57]

Салдары

«Күшті адамға» диктаторлық билік беру көбінесе жаман саясат болып табылады және әдетте қатты көңіл қалдыруға әкеледі, бұл Вильгельм IV-нің қысқа стаддинатерінен кейін тағы бір рет дәлелденді. Ол дереу барлық провинцияларда мұрагерлік «генерал-стадтхольдер» болды Уильям V, апельсин ханзадасы, сол кездегі үш жыл. Әрине, оның анасына дереу регенттік айып тағылды және ол көптеген өкілеттіктерін Бентинкке және оның сүйіктісіне берді, Брунсвик-Люнебург герцогы Луи Эрнест. Герцог Одақтың генерал-капитаны болып тағайындалды (бірінші рет тұрақсыз адам толық атаққа қол жеткізді; тіпті Марлборо да лейтенант- генерал-капитан) 1751 жылы және 1766 жылы Уильямның жетілуіне дейін осы қызметті атқарды. Ол бақытты регрессия емес еді. Оған Республика әлі көрмеген шектен тыс сыбайластық пен тәртіпсіздік тән болды. Бұл үшін герцогті толығымен кінәлауға болмайды, өйткені ол жалпы жақсы ниетті болған сияқты. Бірақ қазір барлық күштің фриз дворянына ұқсас есепсіз аз адамның қолында шоғырланғандығы Douwe Sirtema van Grovestins, билікті асыра пайдалануды ықтималдығы жоғарылатты («Нағыз бостандықты» жақтаушылар жиі ескерткен болатын).[58]

Жаңа стадтлердің жасы келгеннен кейін герцог көлеңкеге шегінді, бірақ құпия Acte van Consulentschap (Кеңес беру актісі) оның жас әрі шешуші емес ханзадаға әсерін жалғастыруды қамтамасыз етті, ал Бентинк өз ықпалын жоғалтты. Герцог өте танымал болмады (ол қастандықтардың нысаны болды), бұл сайып келгенде оны Қатысушы мемлекеттердің жаңа көрінісі талабымен жоюға әкелді: Патриоттар. Ханзада енді жалғыз басқаруға тырысты, бірақ оның құзыреті жетіспейтін болғандықтан, ол тек өз режимінің құлдырауын тездете алды. 1747 ж. Топтық зорлық-зомбылықты епті пайдалану арқылы алынған нәрсені 1780 жж. Басында және ортасында халық толқуларын ептілікпен пайдалану арқылы алып тастауға болады. Қате қарау Төртінші ағылшын-голланд соғысы Стадхольдтер республикада саяси және экономикалық дағдарысты туғызды, нәтижесінде 1785-87 жылдардағы Патриоттық революция болды, ол өз кезегінде Пруссияның араласуымен басылды.[59] Ханзадаға автократиялық үкіметті тағы бірнеше жыл бойы 1795 жылы қаңтарда француз революциялық әскерлері басып кіргеннен кейін қуғынға шығарылғанға дейін жалғастыруға мүмкіндік берді. Батавия Республикасы болу[60]

Әдебиеттер тізімі

- ^ Бұл күн Григориан күнтізбесі сол кезде Голландия Республикасында болған; сәйкес Джулиан күнтізбесі, сол уақытта Англияда қолданылған, қайтыс болған күні 8 наурыз

- ^ Шама, С. (1977), Патриоттар мен азат етушілер. Нидерландыдағы революция 1780–1813 жж, Нью-Йорк, Винтажды кітаптар, ISBN 0-679-72949-6, 17ff бет.

- ^ cf. Фруин, пасим

- ^ Фруин, 282–288 бб

- ^ Фруин, б. 297

- ^ Бұл есептік жазба мыналарға негізделген: Мельвилл ван Карнби, AR «Prinsdom Oranje нұсқасы», in: De Nederlandse Heraut: Tijdschrift to he geied van van Geslacht-, Wapen-, and Zegelkunde, т. 2 (1885), 151-162 бб

- ^ Фруин, б. 298

- ^ Шельдт сағасы Голландия аумағымен қоршалған Мюнстер бейбітшілігі бұл халықаралық емес, голландтық ішкі су жолы екенін мойындады, өйткені бұл 1839 жылдан кейін болады. Нидерландтар Антверпенге жіберілетін тауарларға кедендік баж салығын салды, тіпті мұндай тауарларды голландтық зажигалкаларға арналған сауда кемелерінен беруді талап етті. Антверпен сапардың соңғы кезеңіне арналған. Бұл Антверпен саудасын ілгерілетуге аз ықпал етті және бұл қаланың Амстердам пайдасына жетекші сауда империясы ретінде құлдырауына себеп болды

- ^ Израиль, б. 969

- ^ Израиль, б. 972

- ^ Израиль, б. 971-972

- ^ Израиль, б. 971

- ^ Израиль, б. 973

- ^ Израиль, 973-974, 997 б

- ^ Израиль, 974-975 б

- ^ Черчилль, В. (2002) Марлборо: оның өмірі мен уақыты, Чикаго Университеті, ISBN 0-226-10636-5, б. 942

- ^ Черчилль, оп. cit., б. 954-955

- ^ Черчилль, оп. cit., б. 955

- ^ Израиль, б. 975

- ^ Сабо, И. (1857) XVI ғасырдың басынан қазіргі уақытқа дейінгі қазіргі Еуропаның мемлекеттік саясаты. Том. Мен, Лонгмен, Қоңыр, Жасыл, Лонгманс және Робертс, б. 166

- ^ Израиль, б. 978

- ^ Израиль, б. 985

- ^ а б Израиль, б. 986

- ^ Слингландт, С. ван (1785) Staatkundige Geschriften

- ^ Израиль, б. 987

- ^ Израиль, 987-988 бет

- ^ Израиль, б. 988

- ^ Израиль, б. 989

- ^ Израиль, б. 991

- ^ Израиль, 991-992 бет

- ^ Израиль, 992-993 бет

- ^ Израиль, 990-991 бет

- ^ Израиль, 993-994 бет

- ^ а б c г. Израиль, б. 1002

- ^ Нидерланд флотының салыстырмалы түрде құлдырауы Англиямен жасалған теңіз келісімшартына сәйкес болды, өйткені жуырда жаулап алынды, енді қауіп төндірмейді - 1689 ж. Сәйкес флоттардың өлшемдерінің арақатынасы 5: 3 деп анықталды. Бұл сол кезде өте ұтымды болып көрінді, өйткені Республика өзінің құрлық күштерін құруға шоғырланғысы келді және осы стратагма бойынша өзінің клиент-мемлекеті Англияны теңіз саласында стратегиялық үлес қосуға мәжбүр етті: Англия әр 3 кемеге 5 кеме жасауға міндетті болды жаңадан салынған голландиялық кемелер. Алайда, 1713 жылғы көзқарас бойынша ол Ұлыбританияға республика жасай алмайтын әскери-теңіз артықшылығын берді, әсіресе оның қаржылық қиындықтарын ескере отырып

- ^ Израиль, б. 1003; Фриз, Дж. Де, Вуд, А. ван дер (1997), Бірінші заманауи экономика. Голландия экономикасының табысы, сәтсіздіктері және табандылығы, 1500–1815 жж, Кембридж университетінің баспасы, ISBN 978-0-521-57825-7, б. 142

- ^ Израиль, 1007, 1016–1017 бб

- ^ Израиль, 1014–1015 бб

- ^ Израиль, 993, 996 б

- ^ Израиль, б. 1000

- ^ Израиль, 1006–1012 бет

- ^ Израиль, б. 994, фн. 87

- ^ Израиль, б. 995

- ^ Израиль, б. 994

- ^ Израиль, б. 996

- ^ а б Израиль, б. 997

- ^ Израиль, б. 1067

- ^ Израиль, б. 1068

- ^ Израиль, б. 1069

- ^ Израиль, б. 1070

- ^ Израиль, б. 1071

- ^ Израиль, 1071–1073 бб

- ^ Израиль, 1072–1073 бб

- ^ Израиль, б. 1074

- ^ Израиль, б. 1075

- ^ Израиль, б. 1076

- ^ Израиль, б. 1078

- ^ Израиль, 1079–1087 бб

- ^ Израиль, 1090–1115 бб

- ^ Израиль, 1119–1121 бет

Дереккөздер

- (голланд тілінде) Фруин, Р. (1901) Geschiedenis der staatsinstellingen in Nederland tot den val der Republiek, М.Ниххоф

- Израиль, Дж. (1995), Нидерланды Республикасы: оның өрлеуі, ұлылығы және құлауы, 1477–1806 жж, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-873072-1 hardback, ISBN 0-19-820734-4 қағаз мұқабасы